As the lights dim and the screen comes alive and we are embarked on the journey of two “laapataa ladies” (Phool and Jaya), we hear the insightful words of Manju Maasi to Phool: Iss desh mein sadiyon se ladkiyon ke saath ek fraud chal raha hai. Aur uska naam hai bhale ghar ki beti”. These powerful words of an old stall owner in a railway station illustrate the core message that Rao seeks to drive home with the film: the message of challenging the vicious patriarchy which is an entrenched part of the Hindi hinterland culture. Set in the fictious Nirmal Pradesh in 2001, the film follows the stories of two village girls who are swapped during a train journey because of their veils. The veil, in the film, assumes metaphorical and literal significance. Literally, it constricts and confines the woman and metaphorically it invisibilizes the woman, depriving her of her identity and her selfhood. Satire runs through the humor in the film and paves the way for a social commentary on the deep-rooted evils of patriarchy. Gender discrimination is a way of life for the women in the film where prejudice is so ingrained that if a man does not take dowry, he is told that he is full of “khot” or defect. Without indulging in pedagogic feminine discourse or slogan-inducing speeches, Kiran Rao peels off the layers of injustice and addresses the plight of innocent girls like Phool and Jaya.

In the film we meet two couples, the very innocent and in-love Phool and Dipak and the mismatched Jaya and Pradeep. The beauty of the film lies in this dual depiction of both marriages and men: while on the one hand, we have the naive Phool who is loved and cherished by Dipak, a simple and wonderfully big-hearted man, on the other hand, we see the clever Jaya trapped in a loveless alliance with the nefariously greedy and sinister Pradeep. This is one feminist film where all men are not vilified ogres or monsters. Instead, the film very credibly shows us, through the character of Dipak, that men can be wonderful. Dipak is progressive and liberal in both thought and action. Frantic after he discovers the swapping of the wives, Dipak runs from police station to politicians to railway platforms in search of his beloved Phool, the girl who he barely knows yet has become strongly attached to. For Phool, hardly out of her teens, to be stranded on a strange railway platform without her husband and protector is the worst of all nightmares. Confused and bewildered, she runs into Chotu who takes her to the station master; further confusion ensues as Phool is unable to even name her own village let alone the village of her in-laws. All she does remember is that the village is named after a flower. Chotu, in a hilarious turn of events, proceeds to name flowers one by one: Champa, Chameli, Dhatura., finally conceding, Phulwari ka sab phool khatam ho gaya par ye Phoolkumari ka sasural nahi mila. Finally, Phool is taken by Chotu to Manju Massi’s stall at the station where she slowly evolves under the matriarch’s influence: it is Manu Massi who makes her understand the hypocrisy of values she has been reared under. Slowly, Phool begins to question the training she has been given, wondering why girls are not given any “mauka” or opportunities and why they are made “lachar” or victims. Manju Maasi shows Phool her own capabilities and makes her realize the value of earning her own money.

Juxtaposed with Phool is the resourceful and feisty Jaya, the girl who desires a degree in organic farming so that she can transform agricultural techniques in her region. Willing to go to any lengths to gain an education and stand on her own feet, Jaya sees her swapping as an escape from the despicable Pradeep. She sells her jewels for her admission fees; Kiran Rao poignantly underscores the tactics girls have to resort to in rural India to gain the basic right of being educated, of being self-reliant. Even as Phool evolves under the tutelage of Manju Massi, Jaya helps the women around her evolve. We see how she makes Dipak’s sister-in-law realize how talented an artist she is and convinces Dipak’s mother to cook her favorite dish (“Kamal Kakri ki sabzi”) for herself even if her husband and son do not like it. Interspersed with the protagonists is an ensemble cast of minor figures who are as endearing as the main characters: there is the character of Ravi Kishan, the policeman who is willing to take bribes to file FIRs but who refuses to let Pradeep manhandle Jaya. Then there is the indomitable Manju Massi who speaks some of the most profound truths in the film; in her imitable style, Manju Massi educates Phool about one of the greatest lessons of life: “Apne Saath Khush rehana bahut mushkil ka kaam hai par ek baar ye koi seekh le to koi tumhe dukh nahi phoucha sakta”.

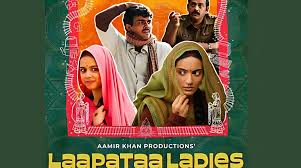

Heartfelt performances by the three debutantes and soulful music combine to make Laapataa Ladies a rare gem: a film that breaks the boundaries of stereotypes and entertains its viewers. Rich in color and rusticity, the film showcases the social culture of the Hindi heartland brilliantly. The film shows two faces of mutiny in women: in Jaya it is because of a genuinely bad husband while in Phool it is because of the circumstances she finds herself in. Yet, both women assert themselves in the midst of a crisis and that is where their triumph lies. The light-hearted touch in the film never lets it get bogged down by weighty preaching; instead, the film simply tells a story of two different women and through this story highlights the subjugation of women and the destruction of their dreams post marriage. Kiran Rao eschews any form of excess and in doing so drives her message home deeper. The evils of dowry, domestic violence and gender stereotypes are all touched upon by Rao without any fanfare or clamor. Ultimately, the” Laapataa Ladies” find themselves and in doing so rehabilitate not only their lives but also the lives of those around them. In a heartwarming scene, we see Manju Maasi eating the sweet made by Phool in sheer joy after Phool reaches her home. Jaya secures her own victory as she rides off to Dhera Dun for her farming degree with the blessings of Dipak and his family. The end of the film feels good because it shows us that emancipation for women is very much a real possibility and that to counter every chauvinistic Pradeep there is a loving and liberal Dipak. As Dipak says to Jaya at the end, “Sapnay dekhna kabhi galat nahi hota.